Life at Dulwich College 1914 – 1919

How did life at Dulwich College change during the World War One? In many respects it didn’t. The boys were educated according to the curriculum of the day, they sat exams and brought home reports at the end of term. They continued to play sports, sing in the choir and take part in drama productions, albeit on a reduced scale. There can be no doubt, however, that the war placed an enormous strain on school life. While Dulwich tried to adopt the approach of ‘business as usual’ there were inevitable changes in the daily life of the College.

Most significantly, the boys, like all children throughout the country, were seeing their fathers, brothers and uncles enlisting in the army. They were also experiencing other Alleynians and masters going to war. Certainly, older boys had no expectation of the future except to go to war and probably get killed. The War Office was taking into the army boys aged 17 and a half. By 1916 all Dulwich boys from the age of 15 were receiving 10 hours of military training per week. Unsurprisingly, membership of the Officer Training Corps increased from 262 in 1914 to 425 in 1917.

Master of Dulwich College, 1914-1928

Only a few weeks before war was declared, the new Master, George Smith, took up his post. He led the College through the war years and later described his first five years as ‘one long nightmare [of] anxiety, strain and sorrow.’

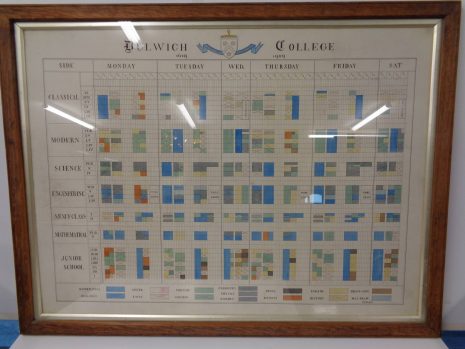

So how was the College organised and what was were the boys learning? In 1914 there were 709 boys at Dulwich College. Of these 106 were boarders and 603 were day boys. There were 40 teachers. The basic annual fee for day boys was £24 and £63 for boarders. Additional fees were charged for such activities as swimming at 5 shillings, OTC at 15 shillings and gym classes also at 15 shillings.

The school was organised into six Sides: Classical, Modern (European History and Modern Languages), Science and Engineering, The Army Class, Mathematics and Junior School. The emphasis had always been on the teaching of Classics but during the war there was an increase in the number of boys entering the Science and Engineering Side. The Sides were abandoned in 1938. In 1914 the boys were distributed as follows:

Junior School 175

Classical Side 162

Modern Side 143

Science and Engineering 186

Army Class 15

Mathematics Class 16

There were three levels of entry – under 11, under 13 and under 15 and candidates were required to sit an entrance exam. A knowledge of basic Latin was required. Boys wishing to enter the Science & Engineering Side were examined in mathematics although the standard of the exam was low.

The number of boys attending the College has been steadily declining since 1910. An inspection by the Board of Education in June 1914 concluded that there had been little improvement in teaching practice since the previous inspection in 1908. Specifically, it was found that masters were virtually autonomous in their classrooms resulting in too much freedom of choice as to subject, books and teaching methods. Indeed, too many masters were teaching subjects which they did not know. Moreover, in terms of new teaching methods the College was lagging behind. The war did nothing to improve things.

By August 1915 eight masters had joined up. George Smith had no choice but to recruit temporary staff including retired masters. Throughout the war there were foreign masters on the staff. The most notable were the German Joerg brothers, John Baptise and John Adam, on the staff for 17 and 23 years respectively. Their presence led to some criticism of the College and they both resigned. George Smith declined their resignations. In 1919, however, the Governors decided ‘not to have masters of foreign origin’ on the staff.

Despite staff shortages school reports continued to be produced throughout the war years.

Probably of greater interest to boys was The Alleynian, in those years very much a schoolboy production. Despite the increasing cost of paper, The Alleynian continued to be published through the war years although it changed in tone and content. Almost every edition carried a Roll of Honour and there was much schoolboy poetry about loss, death and the war.

By 1917 food was scarce in Britain. Nationally, sugar was the first thing to be rationed and Sugar Cards were issued in October 1917. By Christmas there were shortages of butter, margarine and tea. Ration cards for butter and margarine were issued in February 1918. The Buttery, famous for its three-cornered jam tarts, had little to offer apart from tea, ginger bear and buns.

In July 1917 the government Food Controller took out a full page advertisement in The Alleynian. Its request was straightforward enough – EAT LESS BREAD.

Food Controller advertisement in The Alleynian July 1917

When in March 1918 meat was rationed, tripe, nut cutlets and vegetarian lunches were served to boys and staff. The usual practice of serving lunch in the Great Hall was maintained throughout the war.

The College had a tradition of growing food on the grounds. During the war potatoes and vegetables were grown on the College fields, in temporary allotments. In addition, at the height of the country’s food crisis in 1917, 50 boys worked on harvesting camps near Hexham, Northumberland at the request of the National Services Department for six weeks. While the Camp arrangements were satisfactory for the boys, the National Services Department had neither contacted the farmers nor found work for the boys. It fell upon a member of staff and Commanding Officer of the OTC, Captain Hose, to organise the working day. A report produced for The Alleynian states, ‘we did no harvesting – thistle-cutting, turnip-weeding, and timber-cutting were the staple jobs.’

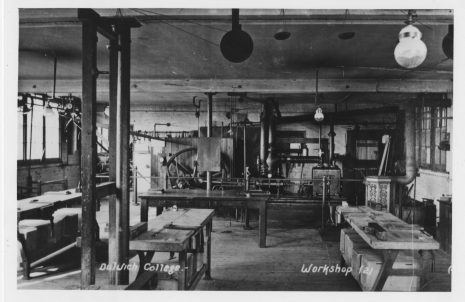

In comparison to the Second World War there was relatively little damage to school buildings. During a Zeppelin raid in 1917 the covered courts were hit and windows in the North Block were blown out. The school agreed to manufacture munitions in the Engineering Workshop as part of the war effort.

Engineering Workshop at Dulwich College

During the war it was common for requests for charitable donations to be published in The Alleynian. Dulwich boys collected all sorts of things as part of the war effort including postage stamps, old razors and books. One of the biggest projects was the raising of funds to buy an ambulance for the Russian Army. In just four months almost £600 was raised from boys, past and present. Between 1914 and 1918 the school raised a total of £950 for various war charities.

A WW1 ambulance on College grounds, possibly that which was purchased to be sent to Russia

The Treaty of Versailles signed on 28 June 1919 officially ended World War One. Dulwich College was at peace once more. There were 691 boys at the school with over 170 names on the waiting list. In October 1919 the first photograph of the whole school was commissioned.